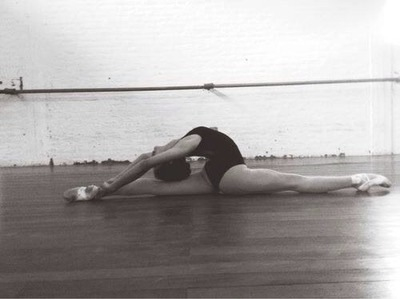

Dancers – are you forcing flexibility?

Dancers, like all athletes, are known as a determined bunch, with an impressive capacity for tunnel vision. Sometimes this determination can backfire, with dancers training through injuries, or pushing the limits of their bodies in unsafe ways. Particularly in the young dancer, there is a huge capacity for injury when striving to reach the flexibility seen by dancers on TV, twitter or instagram.

Every dancer knows the familiar pain of a pulled muscle from pushing too far into a stretch, but most dancers don’t know the bigger more serious consequences of forcing flexibility. As Lisa Howell (Dance Physiotherapist, www.theballetblog.com) once said, pushing into a stretch is often the slowest and most painful way of achieving flexibility. Its also the way in which you are most likely to injure yourself. Dancers need to look after their bodies, as they are the instrument of their craft, and you can’t replace it if it becomes damaged. With young dancers this is even more important, as the average recreational dancer stops dancing after leaving school around 18, but they have more than 60 years left with which to live in their body.

When performing static stretches (the type where you sit in a stretch and hold it) there is a principle known as the path of least resistance. This means that between all the muscles, tendons and ligaments that support the joints in your body, the part that is already the most mobile, will stretch the most, while the stiffer tissues are stretched the least. This often leads to instability in joints that are already lax, while the stiff joints that need increased mobility, stay stiff. This is often a contributing factor responsible for dancers finding they aren’t getting any benefit from traditional stretching and is where an individualised programme can be beneficial.

When stretching is successful and greater flexibility is achieved, that is only half of the equation. In order to execute the perfect arabesque or développe á la secondé you need to be able to utilize that range against gravity. This is where strength is important, and ensuring you are recruiting the correct muscles for the job at hand. Using the wrong muscles often leads to muscles strains, while a lack of strength and control can lead to injury.

Stretching should be a part of your warm up and cool down surrounding your dance class. However, how you do this is extremely important. Dynamic stretching, such as grande battements and those with movement through full range can and should be an important part of your warm up, however static stretching should be avoided before class. When you perform a static stretch, you cause your muscle to temporarily lose power for around 30 mins afterwards, meaning you will not be able to perform at your peak during class. Static stretching should be reserved for the end of class, as part of a cool down process. Saving static stretching for the end of class also reduces your likelihood of a muscle strain resulting from stretching.

And I haven’t even touched on the issue of oversplits, which my students can all tell you I am pretty passionate about NOT doing. For further explanation of why, head on over to The Ballet Blog.

These exact same principles apply to gymnasts, aerialists and acrobats. There are many different ways to achieve flexibility and contrary to popular belief, long, sustained, painful stretches are not the best way. Pain does not equal gain. I would much rather see you in the clinic, setting you up to achieve your goals, rather than working with you to regain what you had after an injury. So if you’ve hurt yourself in the pursuit of the perfect split leap, or if you feel like you’re just not getting anywhere, come on in, I would love to help you out.

- Anita Zwart – Physiotherapist (Masterton)